Mallikjuag Island, Nunavut

Thursday, October 23, 2008 at 5:41AM

Thursday, October 23, 2008 at 5:41AM  You have to read the tides right if you want to cross on foot to Mallikjuag Island.

You have to read the tides right if you want to cross on foot to Mallikjuag Island.

So Pootoojoo Elee had called the elder to get the best estimate of when low tide would be.

So Pootoojoo Elee had called the elder to get the best estimate of when low tide would be.

Still when we arrived where we could cross, the tide was already coming in.

Still when we arrived where we could cross, the tide was already coming in.

And Pootoojoo thought it was too late to cross.

And Pootoojoo thought it was too late to cross.

“C’mon,” I called back, hurrying ahead. “We can still make it, can’t we?” I felt like I was rockhopping up San Carpoforo Creek, back home in the Sur.

“C’mon,” I called back, hurrying ahead. “We can still make it, can’t we?” I felt like I was rockhopping up San Carpoforo Creek, back home in the Sur.

But north and south mean something different here.

But north and south mean something different here.

We did make it across, but by now the tide had come up so high that we couldn’t entirely follow along the shore. We had to scramble up the rocky slope. If you click on the photo above, you’ll be able to make out the thin pencil-line of stones where we crossed. Though stones are still visible, had we crossed even ten minutes later, Pootoojoo said we’d have been stuck in places where water would’ve already been rushing above our knees.

We did make it across, but by now the tide had come up so high that we couldn’t entirely follow along the shore. We had to scramble up the rocky slope. If you click on the photo above, you’ll be able to make out the thin pencil-line of stones where we crossed. Though stones are still visible, had we crossed even ten minutes later, Pootoojoo said we’d have been stuck in places where water would’ve already been rushing above our knees.

While on Mallikjuag Island, the tracks we saw ahead of ours were an Arctic silver fox’s, most likely stalking collared lemmings, like the one we saw dart into rocks quicker than a camera click.

While on Mallikjuag Island, the tracks we saw ahead of ours were an Arctic silver fox’s, most likely stalking collared lemmings, like the one we saw dart into rocks quicker than a camera click.

And the skeleton of a beached beluga whale.

And the skeleton of a beached beluga whale.

Pootoojoo saw in the vertebrae the possibility of two or three carved owls.

Pootoojoo saw in the vertebrae the possibility of two or three carved owls.

Several times before and after we had arrived in Nunavut, people who knew told us pointedly to be aware of polar bears.

Several times before and after we had arrived in Nunavut, people who knew told us pointedly to be aware of polar bears.

It was not meant as an idle injunction. This bear was killed near town just a couple days before we arrived. “A small one,” Pootoojoo said. “Probably only seven and a half feet or so.” He has friends who have been mauled.

It was not meant as an idle injunction. This bear was killed near town just a couple days before we arrived. “A small one,” Pootoojoo said. “Probably only seven and a half feet or so.” He has friends who have been mauled.

So I asked the obvious question.

So I asked the obvious question.

“Are you carrying a sidearm in that bag?”

“Something like that,” Pootoojoo said.

“Is it enough to stop a bear?”

“Let’s hope we won’t have to find out,” he said.

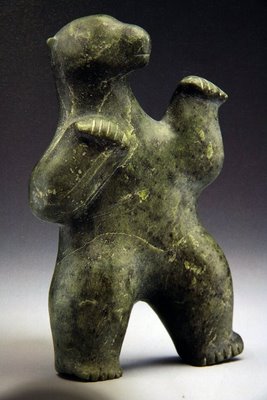

Isaci Etidloi calls this sculpture a man could die at any time.

There are other beings in this land as well. And I was astonished to learn a precise word for them.

There are other beings in this land as well. And I was astonished to learn a precise word for them.

Ijjigait, they are called. The word means those fleeting glimpses you might get out of the corner of your eye -- too fleeting for you to recognize, but they leave you with the vague feeling that one of the old ones might have just appeared.

I shouldn’t speak of them.

But we were approaching the rim of a small lake…

But we were approaching the rim of a small lake…

…ringed with the depressions of sod and stone homes built perhaps two millennia ago.

…ringed with the depressions of sod and stone homes built perhaps two millennia ago.

They’d crib roofs from whale bones and then cover them with skins and sod.

They’d crib roofs from whale bones and then cover them with skins and sod.

People have lived in the Arctic for at least 10,000 years, crossing from Siberia in migrations of a pan-Arctic culture. Thule people, ancestors of the Inuit, arrived during a warming trend a thousand years ago. They hunted bowhead whales and other large sea-mammals from open boats and gradually displaced the earlier Paleoeskimo Dorset culture.

People have lived in the Arctic for at least 10,000 years, crossing from Siberia in migrations of a pan-Arctic culture. Thule people, ancestors of the Inuit, arrived during a warming trend a thousand years ago. They hunted bowhead whales and other large sea-mammals from open boats and gradually displaced the earlier Paleoeskimo Dorset culture.

The Thule and Inuit have been nomadic people living in seasonal camps and hunting sea mammals and following caribou migrations in their qamutiik (dog-sleds) and qajait (skin-covered hunting canoes).

The Thule and Inuit have been nomadic people living in seasonal camps and hunting sea mammals and following caribou migrations in their qamutiik (dog-sleds) and qajait (skin-covered hunting canoes).

Inuits' nomadic hunting life in camps ended only fifty years ago. It’s hard to think of a more accelerated change in a culture.

Inuits' nomadic hunting life in camps ended only fifty years ago. It’s hard to think of a more accelerated change in a culture.

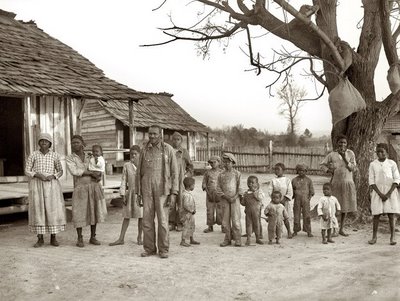

Pauta Saila has lived in both worlds. He was born in a caribou hunting camp in 1916. His father took him everywhere with him, and Pauta learned how to survive out on the land. His father taught him never to rush – but always to wait for the weather. By the time he was sixteen, Pauta was driving a dog-team on his own.

Pauta Saila has lived in both worlds. He was born in a caribou hunting camp in 1916. His father took him everywhere with him, and Pauta learned how to survive out on the land. His father taught him never to rush – but always to wait for the weather. By the time he was sixteen, Pauta was driving a dog-team on his own.

His first wife is in the center of this photograph.

His first wife is in the center of this photograph.

As a carver, Pauta’s signature is the dancing polar bear. He has an affinity for polar bears. If you do not bother them, they will not bother you, he thinks.

As a carver, Pauta’s signature is the dancing polar bear. He has an affinity for polar bears. If you do not bother them, they will not bother you, he thinks.

One day as Pauta sat on his porch smoking, people inside the church across from him suddenly began gesticulating wildly to him. Pauta turned around and saw a polar bear right behind him. Figuring that the bear was interested in the walrus meat being stored outside, Pauta took a piece, reached down, and handed it to the bear. The bear waited patiently, took the walrus meat gently, and wandered off.

Pauta and his current wife, the printmaker and carver Pitaloosie Pudlat Saila, and their great grand-daughter.

Pauta and his current wife, the printmaker and carver Pitaloosie Pudlat Saila, and their great grand-daughter.

In Pauta and Pitaloosie’s kitchen hang these ulus. They serve many functions, including cutting muqtaaq from a whale.

In Pauta and Pitaloosie’s kitchen hang these ulus. They serve many functions, including cutting muqtaaq from a whale.

They are also used for scraping clean sealskin.

They are also used for scraping clean sealskin.

Pauta is the oldest member of his community and hopes to do one more carving.

Pauta is the oldest member of his community and hopes to do one more carving.

Pootoojoo had more he wanted to show us on Mallikjuag Island.

Pootoojoo had more he wanted to show us on Mallikjuag Island.

Like this burial site that is perhaps a thousand years old.

Like this burial site that is perhaps a thousand years old.

The skeleton inside is of an enormous man, Pootoojoo points out. There are sites in Nunavut where such large stones have been moved that anthropologists conjecture that among the peoples who once lived here might have been people who were nearly giants.

The skeleton inside is of an enormous man, Pootoojoo points out. There are sites in Nunavut where such large stones have been moved that anthropologists conjecture that among the peoples who once lived here might have been people who were nearly giants.

Once young men from town disturbed these sites. In fact, one young man took two skulls and kept them in his room. Shortly afterwards he committed suicide, and the elders then returned the skulls where they belong.

Once young men from town disturbed these sites. In fact, one young man took two skulls and kept them in his room. Shortly afterwards he committed suicide, and the elders then returned the skulls where they belong.

The stone cairns on the right are for perching your qajaq off the ground.

The stone cairns on the right are for perching your qajaq off the ground.

If you do not do this, the dogs you’ve brought with you will eat through the sealskin of your canoe.

If you do not do this, the dogs you’ve brought with you will eat through the sealskin of your canoe.

There are many theories about the purposes of these ancient inuksuit. The word means something like made to resemble someone. They can be seen for miles, and among other things, are likely directional markers.

There are many theories about the purposes of these ancient inuksuit. The word means something like made to resemble someone. They can be seen for miles, and among other things, are likely directional markers.

This inuksuk points towards northern fishing camps. A collection of inuksuit gathered together likely indicates that you have come into a particularly powerful place.

In old Inuit stories, when you pass beyond inuksuit, you have truly entered a trackless, wild world.

In old Inuit stories, when you pass beyond inuksuit, you have truly entered a trackless, wild world.

And it was time for us to be heading back ourselves.

And it was time for us to be heading back ourselves.

We had come at the perfect time. It hadn’t gotten cold yet. It was only zero degrees out, and the inlet hadn’t frozen.

We had come at the perfect time. It hadn’t gotten cold yet. It was only zero degrees out, and the inlet hadn’t frozen.

Pootoojoo thought he had arranged for a canoe to pick us up. But no boat was appearing.

Pootoojoo thought he had arranged for a canoe to pick us up. But no boat was appearing.

And he thought there was a chance that a blizzard could be coming in. There had been a blizzard two nights before.

And he thought there was a chance that a blizzard could be coming in. There had been a blizzard two nights before.

We could walk back the way we had come, but the tide wouldn’t be low enough for that for three or four hours more – and it would be plenty dark by then.

Finally, a canoe entered the inlet, coming from the fishing camps further north. Pootoojoo waved a blanket to call the canoe to shore.

Finally, a canoe entered the inlet, coming from the fishing camps further north. Pootoojoo waved a blanket to call the canoe to shore.

And soon we were crossing the inlet again, this time by canoe.

And soon we were crossing the inlet again, this time by canoe.

Not only had the family had a successful weekend at the fishing camp, but the next day they discovered they had also caught a beluga whale in their fishing net tethered in the inlet. There would be a feast that night.

Not only had the family had a successful weekend at the fishing camp, but the next day they discovered they had also caught a beluga whale in their fishing net tethered in the inlet. There would be a feast that night.

Mallikjuag Island,

Mallikjuag Island,  Nunavut | in

Nunavut | in  Artists,

Artists,  Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage